Determining Which Country a Location Is in Without an API (…But With MariaDB)

A few days ago, I wrote about implementing search term highlighting as part of a tool my partner and I have long been using to track our shared purchases. Another set of improvements deals with location data – towards the tail end of our recent vacation to South Korea, on a whim, I added a feature where logging a purchase on a device with geolocation support also captures the current location1 (as a latitude-longitude pair), storing it along with the rest of the purchase data.

But what to do with that data? Displaying it on a map2 is kind of neat, of course.

Places we ate and shopped at in central Seoul. Monami Curry, whose half-half curry is instagrammable to the max, seemingly hasn’t survived the pandemic (in that location, anyway – there’s another branch in Suwon, a bit south of Seoul).

But what else might location data be useful for?

Well, while implementing the search feature I wrote about last time, I got the idea of filtering purchases by country – providing a dropdown menu of country names as part of the search form, selecting one of which constrains search results to purchases 1. with a location that’s 2. located in that country.

The challenge, then, is determining which country a latitude-longitude coordinate pair falls into. There’s roughly two ways to solve this:

-

Calling out to any of the dozens (hundreds?) of reverse geocoding APIs available. That’s easy to do and, given that we’re unlikely to log more than a couple dozen purchases a month, ought to be well within the free tier of most API providers. Slight privacy concerns, but eh. And if the API were to be sunset in a few years, just switch to another one. No-brainer, really.

-

Saying “I don’t need no stinkin’ API”, procuring a GeoJSON file containing country outlines, massaging it into a format and detail level appropriate for the task, importing it into a data structure, building a way to query that data for polygon-point intersections, then bulk-processing existing purchases to add country names.

No points for guessing which option I picked!

Disclaimer: Countries are weird (but it doesn’t really matter)

There’s 200ish countries. Countries can be divided into multiple parts, sometimes separated by roughly half the planet. A few countries have (potentially nested) exclaves in other countries. There’s places that are sort of shared between multiple countries. Other places are claimed by no one. Many borders are disputed, so which country a location belongs to depends on who you ask. Similarly, some countries wholly don’t exist according to other countries. And coastlines tend to be fractals.

…but my partner and me are unlikely to make purchases in most of those areas, so correct treatment of edge cases like this wasn’t3 a priority when selecting a dataset.

GeoJSON and lists of lists of lists (of lists)

There’s a bunch of formats that geographical data like country outlines commonly come in – for example, ærialbot, a Mastodon bot I wrote a few years back, utilizes a Shapefile to generate random locations in the non-ocean parts of the world. These days, GeoJSON seems to be more popular (and thus more widely supported), and it’s easier4 to inspect and edit in its raw form.

That’s because a GeoJSON file is basically just a list of polygons (or multipolygons – handy for encoding non-contiguous shapes, e.g., Greece), each of which can be annotated with data like, say, a country name. Other geometry types like points are also supported, but they’re not relevant for storing country borders.

{

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"features": [ // a list...

{

"type": "Feature", // ...of features...

"geometry": { // ...each of which has a geometry...

"type": "MultiPolygon", // ...here, of type multipolygon...

"coordinates": [ // ...which is just a list of polygons...

[ // ...where each polygon is a list starting with a main shape...

[ // ...specified as a list of longitude-latitude coordinate pairs...

[-17.2448353, 21.3521298], [-17.5584441, 21.2683253], ...

],

[ // ...followed by zero or more holes (which are also polygons)...

...

],

... // ...more holes go here...

],

[ // ...another polygon...

[ // ...with a main shape (no holes this time)...

[..., ...], ...

]

],

... // ...even more polygons...

]

},

"properties": { // ...and some data

"osm_id": -5441968,

"name": "República Árabe Saharaui Democrática الجمهورية العربية الصحراوية الديمقراطية",

"name_en": "Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic",

...

}

},

... // more features, each like the one above!

]

}

If you’re confused about the difference between polygons, multipolygons, and holes (…I was!), here’s a Stack Exchange post explaining and illustrating these concepts really well.

Foraging for (or, depending on your disposition, hunting down) country outline data

Using the search engine of your choice, you can find a bunch of sites providing freely-downloadable GeoJSON files of the world’s borders at varying levels of detail – here’s one I initially considered. (You don’t want too much detail because that makes for larger files and slower computation, and you don’t want too little either because that’ll lead to inaccuracies.)

Most datasets I found delimit countries by their coastlines, which makes a lot of sense for your typical world map! But that’s not ideal for a reverse geocoding use case since 1. when you’re near the coast, GPS inaccuracies can place your location just barely in the sea (and thus beyond the country outline), 2. depending on the resolution of a given GeoJSON file, small islands and peninsulas might not be included, 3. land reclamation is a thing, so coastlines change relatively rapidly in certain areas, and 4. accurately tracing the coastlines significantly increases the volume of data for some countries (e.g., again, Greece) when simple shapes around small islands would suffice for this use case.

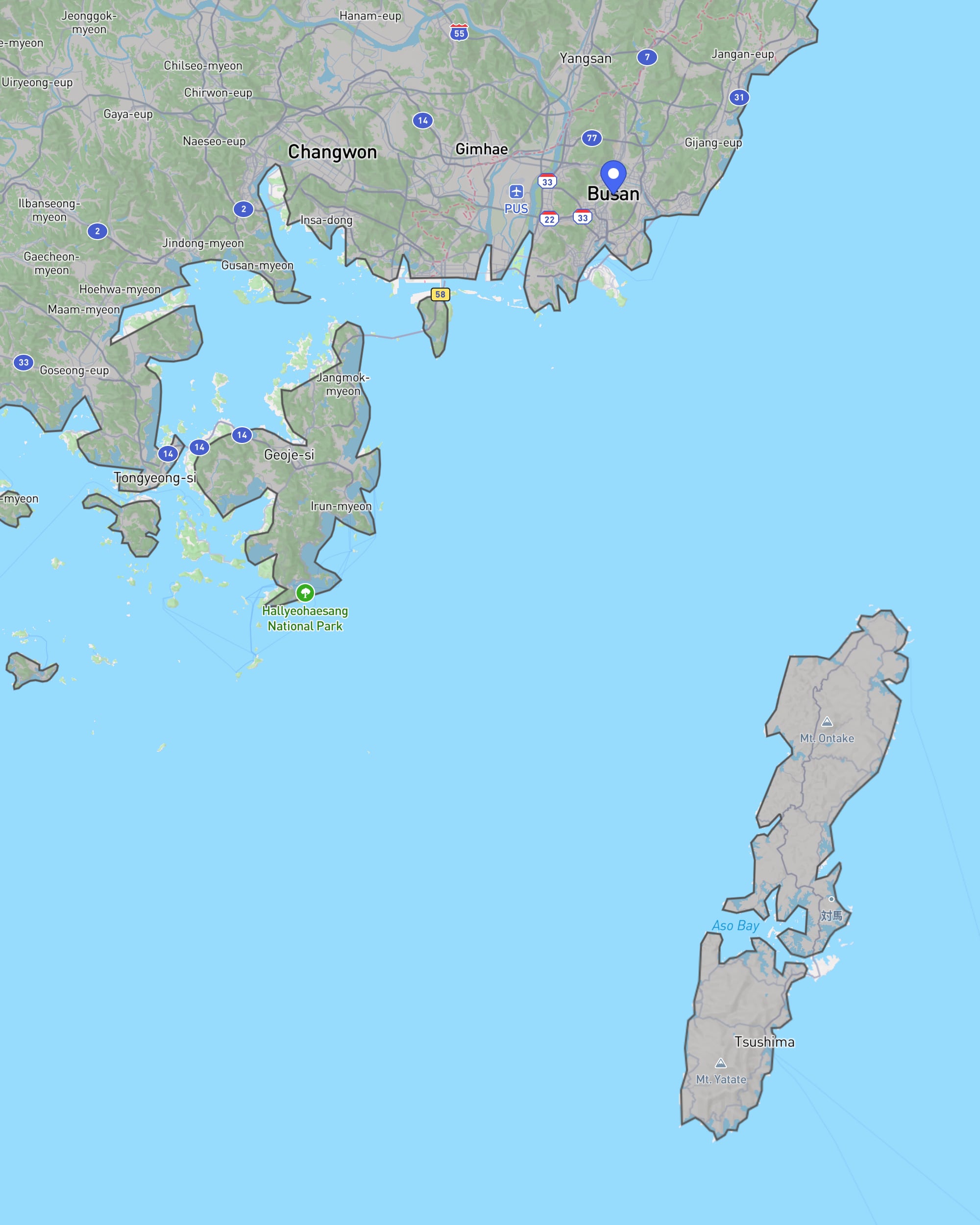

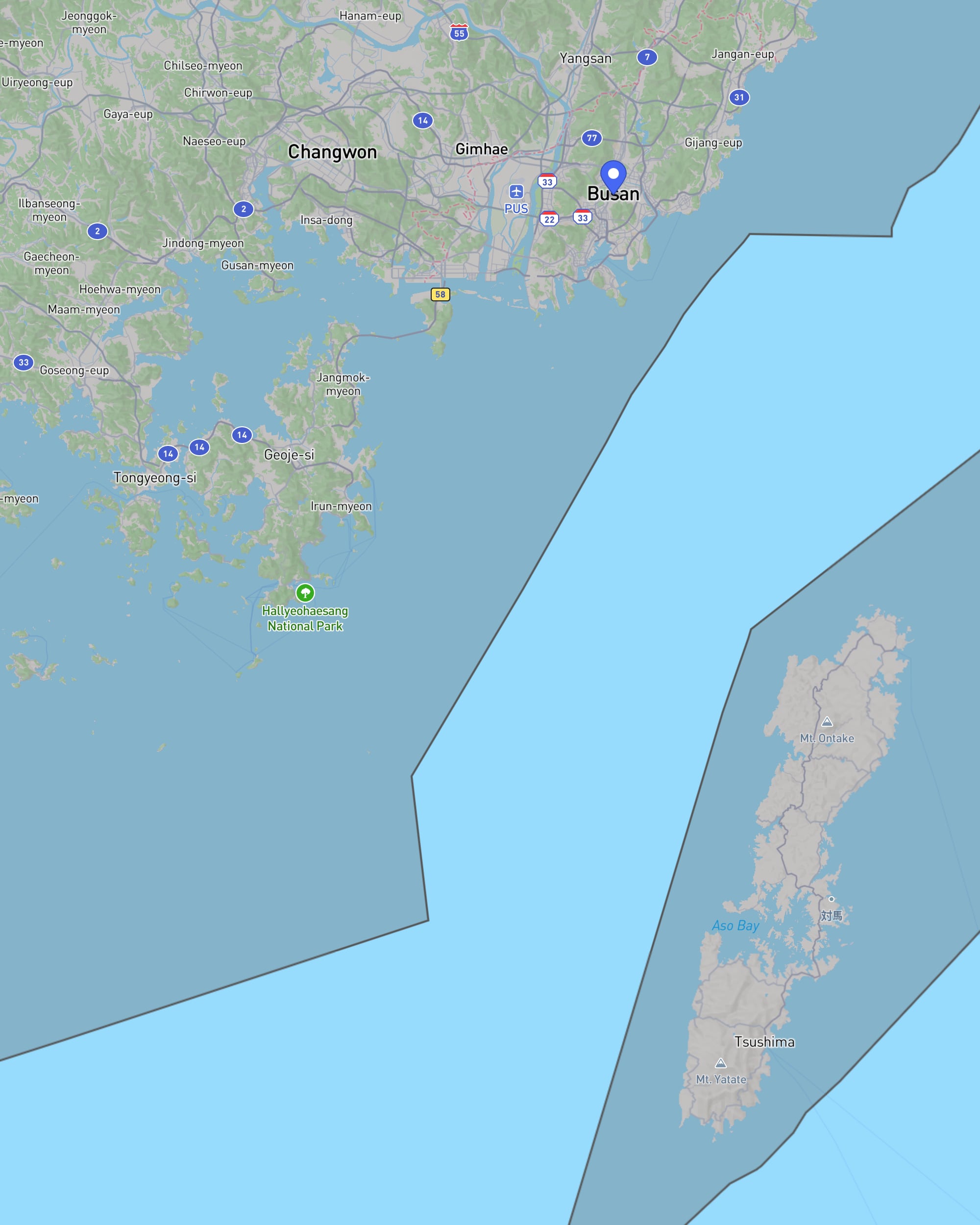

The difference between a coastline-delimited dataset (fairly low-res, mind you) and one based on territorial waters. (Rendered using geojson.io, background map courtesy of Mapbox/OpenStreetMap.)

So I looked for a dataset that includes a country’s territorial waters. It’s possible to generate such a dataset using OpenStreetMap’s Overpass Turbo API, but following a link from a Stack Exchange post that explains how to do that, I instead came across osm-boundaries.com, a service offering ready-made country-plus-territorial-waters outlines for download. Selecting all countries yielded a 125 MB GeoJSON file, which seemed5 a bit larger and more detailed than what I actually needed.

Luckily, there’s Mapshaper, an excellent web-based software for editing geospatial data (and converting it between various formats). Among other features, it comes with a simplification tool which allowed me to remove excessive detail while keeping land borders within about 10 meters of their actual locations, with the resulting file6 weighing in at a more-manageable 23 MB.

Checking if a polygon contains a point (and why I didn’t need to implement that)

Given the GeoJSON file I prepped above and a location from my tool’s database, how can I determine which country contains that location? Easy: For all polygons in the GeoJSON file, do a point-in-polygon check (while essentially inverting that check for holes) and return the (hopefully single) polygon that matches.

…so how to do a point-in-polygon check, then?

Since that’s a common task in computer graphics (among other fields), there’s a whole bunch of algorithms tackling it.

- Ray casting algorithm: Casting a ray from outside the polygon towards the point and counting how many times it intersects the edge of the polygon – if odd, the point’s inside the polygon.

- PNPoly: As far as I can tell, this is just a battle-tested implementation of the ray casting algorithm.

- Winding number algorithm: Computing the point’s winding number with respect to the polygon – i.e., by how many degrees the edge of the polygon, considered segment by segment, travels around the point. If non-zero, the polygon contains the point.

When checking multiple polygons (a list of countries, say), I assume (but haven’t read up on it) that you could do some preprocessing before dropping into one of the algorithms listed above, e.g., using some kind of spatial tree structure to narrow down the number of polygons to test, then first testing whether the point falls into a given polygon’s axis-aligned bounding box, which is computationally inexpensive.

Since my tool is built with PHP (and, as custom dictates, MariaDB7 – this’ll be relevant in the next paragraph), I started looking for PHP libraries providing point-in-polygon algorithms. There’s a few implementations, but the ones I found don’t natively support GeoJSON input, requiring at least a modicum of data munging.

Who needs a geospatial library if you’ve got a database?

Remembering that PostgreSQL – my usual database of choice – has excellent geospatial capabilities thanks to PostGIS, I looked into whether there’s a similar extension for MariaDB. There isn’t – because all kinds of geospatial functions are just built in, including one for point-in-polygon checking! And what’s more, MariaDB provides a function that converts GeoJSON data8 into its internal representation. How handy is that?!

So I wrote a quick little PHP command-line script that…

- …creates a database table

countrieswith two columnsnameandoutline, the latter of which will hold the corresponding (multi)polygon encoding the country-plus-territorial-waters border. - …imports a GeoJSON file formatted as shown above into that table (due to limited familiarity with GeoJSON files, I assume other files might not work – luckily, as discussed, you can inspect them easily and make the necessary adjustments to the code below).

- …goes through my preexisting

purchasestable, annotating any rows that have location data with the matching country name – here, you’ll see how to query thecountriestable.

“Talk is cheap. Show me the code.”

Okay, okay, Linus Torvalds, here it is, step by step, with quite-possibly-redundant explanations below each code block. First, a few lines of setup.

const GEOJSON_FILE = "OSMB-ab12e27d758279c6311e8bd945a358d9a594bc44.json";

PHP_SAPI === 'cli' or die('run via cli only'); // allow execution via cli only

require_once "db.class.php"; // import meekrodb

DB::$user = "...";

DB::$password = "...";

DB::$dbName = "...";

A little less than ten years ago, when I built the initial version of our purchase tracker, it was common practice to access MariaDB databases using a library like MeekroDB instead of directly utilizing the functions built into PHP – and since my PHP knowledge has atrophied in the intervening years (and MeekroDB was already in my project directory, anyway), I’m just doing the same here.

DB::query("DROP TABLE IF EXISTS `countries`;");

DB::query("CREATE TABLE `countries` (`name` text, `outline` geometry);");

Creating the table is fairly straightforward. What’s neat is that MariaDB’s geometry type encompasses all kinds of geospatial data – so there’s no need to insert polygons differently into the table than multipolygons, say.

$geojson = json_decode(file_get_contents(GEOJSON_FILE));

foreach ($geojson->features as $feature) {

$name = $feature->properties->name_en;

$outline = json_encode($feature->geometry);

DB::query("INSERT INTO `countries` (`name`, `outline`) VALUES (%s, ST_GeomFromGeoJSON(%s));", $name, $outline);

}

These six lines import the data contained in the GEOJSON_FILE into the countries table. First, the GeoJSON data is parsed into a PHP object representation, each feature (i.e., country) of which is then processed in succession: its name is extracted, its geometry is “re-JSON-encoded” for transfer to the database, then these two values are INSERTed into the countries table, taking advantage of the ST_GeomFromGeoJSON() function to convert the GeoJSON geometry into MariaDB’s internal representation.

With country outlines now persisted in the database, all that was left to do was updating existing purchases (and, but there’s no point in showing this here, updating my tool to determine the country of newly-logged purchases):

$purchasesWithLocation = DB::query("SELECT * FROM `purchases` WHERE `latitude` IS NOT NULL AND `longitude` IS NOT NULL");

The purchases table has latitude and longitude columns which are NULL on purchases without location data.

foreach ($purchasesWithLocation as $p) {

$point = '{"type": "Point", "coordinates": [' . $p["longitude"] . ', ' . $p["latitude"] . ']}'; // careful: lon, lat!

DB::query("UPDATE `purchases`

SET `country` = (SELECT `name`

FROM `countries`

WHERE ST_Contains(`outline`, ST_GeomFromGeoJSON(%s))

ORDER BY `name`

LIMIT 1)

WHERE `id` = %i", $point, $p["id"]);

}

This code snippet assembles a GeoJSON feature of type Point representing each purchase’s location. The UPDATE statement’s subquery over the fancy new countries table utilizes the ST_Contains() function to check if any given country’s outline contains the specified point, yielding either a single value (the country’s name) or NULL if no match was found. The result of the subquery is then patched into the relevant row of the purchases table.

How’s performance looking? On my excellent shared hosting plan and given the GeoJSON data prepared above, the ST_Contains() function takes at most a second per check – usually, it’s significantly quicker.

-

After returning from vacation, I implemented location refinement by moving a marker on a map. This interface has also allowed me to add locations to some previous purchases. ↩

-

Which may change in future depending on geopolitical developments. ↩

-

Shapefile’s a binary format, GeoJSON is just JSON (with a schema). ↩

-

Based on nothing but intuition – at this point, I had yet to think about how to actually query this data. ↩

-

I’d’ve been happy to provide a download link, but I’m not sure about licensing – so drop me an email if you’re interested. ↩

-

Formerly known as MySQL. (Which still exists, but there’s little reason to use it over MariaDB these days.) ↩

-

I’m linking to MySQL’s documentation here because it’s more detailed – I suppose (yet have some difficulty typing this) there’s some benefits to using Oracle products. ↩