Controlling the Settings in Chrome's Print Dialogue With CSS

When’s the last time you’ve printed a website? If you’re anything like me, that query will return either “long ago” or some kind of NULL value1 – but the print functionality built into modern browsers isn’t just tremendously handy for precise spilling of black water on dead wood, it can also be coerced into serving as a simple-yet-powerful export-to-PDF method for basic client-side document generators or even server-side applications. For example:

-

My project markdeep-slides, which builds on top of the in-browser Markdown renderer Markdeep to enable seamless, setup-free presentation slide authoring and playback, relies on the browser’s built-in print tooling for PDF exporting.

-

Similarly, markdeep-thesis, whose initial development was part of my Master’s thesis (for the purpose of typesetting it), would be pointless without solid in-browser printing.

-

Because I’m incorrigible2, I’ve also formatted my personal resume and cover letter template (based on Min-Zhong John Lu’s html-resume) using HTML and CSS – impossible without confidence in the browser’s print functionality. In this case, I was using a good old-fashioned Makefile to generate PDFs using a headless instance of Chrome. (More about that at the bottom of this post.)

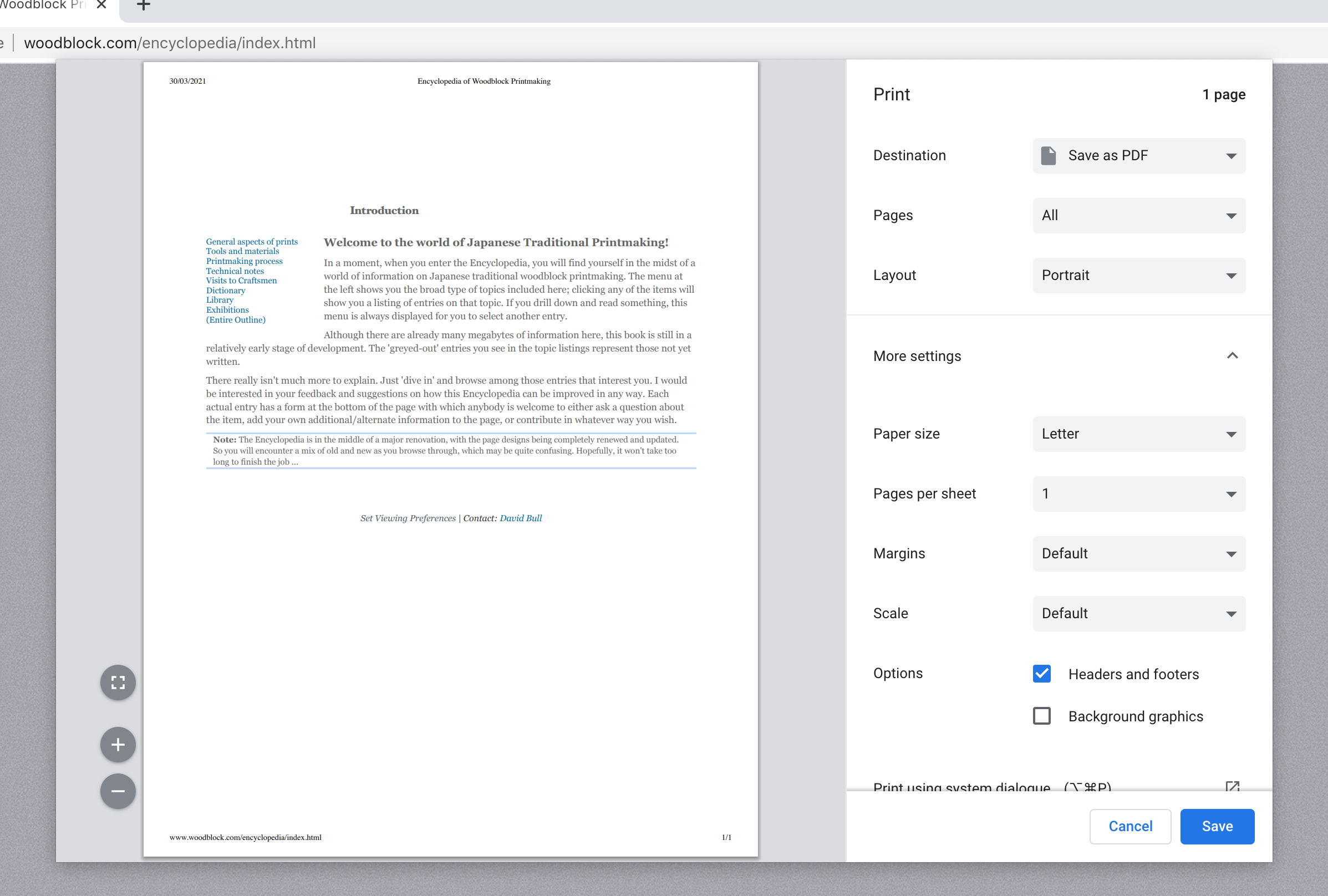

But browsers like to futz with your page en route to generating a PDF: With the best intentions, they add additional margins, fill them with some metadata that you don’t want on your generated document, and get rid of all the background colors. Great for printing, but not at all what you want on your bespoke PDF! Take a gander at this badly cropped screenshot of Chrome’s Print dialogue:

Chrome’s Print dialogue (as it appears on a Mac in early 2021) showing a preview of, appropriately enough, David Bull’s Encyclopedia of Woodblock Printmaking, with all settings set to their defaults.

Out of this plethora of options, five can be directly or indirectly controlled via CSS: Layout, paper size, Margins, Headers and footers, and Background graphics.

In this post, I’ll be focusing on Chrome simply because of all major browsers, its printing tooling has followed web standards more closely than others’ for at least the last couple of years. Crucially, as of early 2021, non-Chromium-based browsers don’t allow for specifying arbitrary paper sizes with CSS – which is the first thing we’ll be looking at.

At the end of this post, I’ll also write about other CSS features of relevance in a printing context, plus how to print to PDF using headless Chrome.

Setting the “paper” size

You shouldn’t dictate the paper size on any old website – after all, the user might have their own preference. However, this CSS feature comes in handy when the desired paper size is known, say, in the context of markdeep-thesis where it’s configurable by the user in the source code, or for markdeep-slides, where you want precisely one slide per page, so the paper size needs to exactly match the slide aspect ratio.

Inside CSS’s @page selector, you can specify a size property whose value determines the paper size. Any of the following declarations will work – there’s almost certainly something for your use case:

@page {

/* Browser default, customizable by the user in the print dialogue. */

size: auto;

/* Default, but explicitly in portrait or landscape orientation and not user-

customizable. In my instance of Chrome, this is a vertical or horizontal letter

format, but you might find something different depending on your locale. */

size: portrait;

size: landscape;

/* Predefined format, can be coupled with an orientation. */

size: letter;

size: A4;

size: A4 landscape;

/* Custom, with same width and height. */

size: 10cm;

size: 420px;

size: 6in;

/* Different width and height. */

size: 640px 360px;

size: 20cm 15cm;

}

According to caniuse.com, this feature only works in Chromium-based browsers like Chrome, Edge, and Opera – both Firefox and Safari don’t implement it at all.

Because I know you’re going to ask: You can nest the @page selector inside a @media print query – after all, the paper size is only ever going to be relevant in a printing context – but not using this media query won’t break anything.

Adding or removing margins

Similarly, this is useful if your document already contains the margins you want, in which case you’d like to zero out any additional margin the browser would add. As an added perk, setting the margin to zero will hide the default header and footer lines your browser renders on each page – there’s not enough space for them.

@page {

/* No margin, hide the header and footer. */

margin: 0;

/* Some margin. Header and footer will be shown if the browser thinks there's

enough space (in my ad-hoc tests, anything larger than 8mm will trigger them). */

margin: 1in;

/* Different margins vertically and horizontally. */

margin: 2cm 4cm;

/* Wildly different margins – the order matches the standard CSS margin property:

north, east, south, west. */

margin: 1cm 2cm 3cm 4cm;

/* You can also specify single margins only. */

margin-left: 20pt;

}

According to caniuse.com, this feature works in Chromium-based browsers like Chrome, Edge, and Opera, but also in Firefox and – believe it or not! – Internet Explorer, all the way back to IE 8. Safari, meanwhile, has never heard of any of this.

But wait, there’s more! You can target the first page of your document separately using the :first pseudo-class. The same goes for :right (odd-numbered, assuming your document is written in a left-to-right script) and :left (even-numbered) pages.

@page :first {

margin: auto 3cm;

}

@page :left {

margin-left: 4cm;

margin-right: 3cm;

}

@page :right {

margin-left: 3cm;

margin-right: 4cm;

}

This might seem somewhat byzantine – why would one need different margins on left and right pages? – but in book binding, it’s best practice for the two inner margins (i.e., the right margin of the left page and the left margin of the right page) to be equal in appearance, once bound, to each of the outer margins, which may require the adjustments these pseudo-classes enable.

If you make use of these pseudo-classes, Firefox won’t understand you anymore – I trust you’re beginning to see why I added that only-works-in-Chrome disclaimer at the top of this article.

Forcing background colors

All browsers default to not printing background colors to conserve ink – very helpful! If you really need to, you can forcibly re-enable backgrounds on a per-element basis, say, for <code> snippets interleaved with your prose whose light gray background you’d like to preserve.

code {

-webkit-print-color-adjust: exact; /* Chrome/Safari/Edge/Opera */

color-adjust: exact; /* Firefox */

}

This exact mode also disables some browsers’ adjustment of low-contrast elements in print mode.

Nothing’s stopping you from using the * selector here, but think twice before doing so – users who actually print on paper might be disgruntled if you do (but ink salesman will worship you during their secret rituals).

According to caniuse.com, the feature is understood by all major browsers. Yay!

Why rely on the browser’s print functionality at all when there’s jsPDF and similar libraries?

Since the CSS features I’ve discussed in this article are reliant on the user running modern versions of specific browsers, wouldn’t it be neat to have the power of generating a PDF (no matter whether for printing or just reading offline) from a web page in a browser-independent fashion, but still client-side? Why, yes!

There are a bunch of libraries that purport to accomplish this, including jsPDF. They more or less get the job done by implementing custom HTML renderers in JavaScript – a daunting task that doesn’t stand a chance at being fully compatible with evolving web standards: webfonts and advanced CSS features tend to fall by the wayside.

Unless the document you’re trying to generate a PDF of is very simple, it’s not going to look the same as in-browser – which doesn’t matter too much in many contexts, but as any layout and typography perfectionist can attest, is objectively intolerable.

Addendum: Other printing-adjacent CSS features

While writing this article, two additional CSS features that don’t interact with the settings in Chrome’s Print dialogue, yet are highly relevant when designing printable documents, came to mind.

Hyphenantion

The disabled-by-default hyphens property determines how text is hyphenated when it wraps across multiple lines. To ensure correct hyphen placement, specify the language your document is written in – e.g., <html lang="en"> if it’s in English.

p {

-webkit-hyphens: auto;

-ms-hyphens: auto;

hyphens: auto;

}

A more detailed explanation of this functionality and how to manually hint at line break points, along with notes on browser support, are available on MDN. Advanced hyphenation controls are discussed in an article by Richard Rutter.

Controlling page breaks

You might require the browser to avoid breaking a certain element across pages (or columns). For example, you wouldn’t want a <figure> containing an image and its caption to be split across two pages – etymologically speaking, a caption is nary a caption if it’s not keeping tabs on the thing it relates to.

That’s what the break-inside property (the artist formerly known as page-break-inside) is for:

figure {

break-inside: avoid;

}

More details, including browser support, are available on MDN. There’s also the related, if slightly more esoteric, break-before and break-after properties.

Addendum: Printing headlessly

As I prefer Safari over Chrome for day-to-day web surfin’, it’s rather inconvenient to fire up Chrome every time I want to, say, create a PDF version of my resume. Luckily, any recent version of Chrome can run in headless mode – i.e., on the command line and without opening its GUI.

This involves figuring out where your Chrome executable lives – the location will vary from platform to platform. Since I’m on a Mac, mine can be found at /Applications/Google Chrome.app/Contents/MacOS/Google Chrome. Because that’s way too long to type every time, I’ve defined an alias in my .bashrc:

chrome='/Applications/Google Chrome.app/Contents/MacOS/Google Chrome'

Then, in order to generate a PDF file book.pdf from an HTML document manuscript.html, run3:

chrome --headless --print-to-pdf=book.pdf --no-margins --virtual-time-budget=1337 manuscript.html

The --virtual-time-budget=NUMBER flag defines how long4 Chrome waits between page load and printing – this allows the layout to settle and JavaScript code to run. Complex documents might require a value higher than 1337. On some platforms, you might need to supply the --disable-gpu flag as well.

-

Every database engineer’s favorite value – it never causes any trouble, ever, at all! ↩

-

Or, more verbosely: In the process of recently graduating from university, I found myself contemporaneously graduating from wanting to use LaTeX for everything – and surely you’ll understand that a serious programmer can’t possibly write their resume in Google Docs. (Actually, a serious programmer would totally do that because they’d be too busy writing serious programs to bother with the minute details of resume formatting.) ↩

-

You’d think that if there’s a

--no-marginsflag, there should also be flags for configuring the remaining settings that would ordinarily appear in the Print dialogue. Yet, to the best of my knowledge, there aren’t. ↩ -

That’s only an approximation of what happens – the virtual time budget is actually a fair bit more complicated than that. ↩